-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Magnus Baumhäkel, Michael Kindermann, Ingrid Kindermann, Michael Böhm, Soccer world championship: a challenge for the cardiologist, European Heart Journal, Volume 28, Issue 2, January 2007, Pages 150–153, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehl313

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The 18th FIFA Soccer World Cup 2006 in Germany enthused millions of people worldwide, but only little is known about the association of such an event with cardiovascular events. Modest physical activity is known to reduce the cardiovascular risk significantly. On the other hand, vigorous physical activity and emotional strain increase the cardiovascular risk and the incidence of cardiovascular events likely due to an increased sympathetic tone with consecutive catecholamine stimulation of the heart. Few reviews and case-reports are dealing with the risk of physical activity in cardiovascular high-risk patients or athletes with congenital heart diseases (e.g. hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy), but the impact of highly competitive events on cardiovascular events, especially in spectators were rarely addressed. Thus, the increased risk of cardiovascular events in players and spectators were addressed in this review with respect to various soccer matches and tournaments, such as the FIFA World Cup.

The 18th FIFA World Cup took place from 9 June 2006–9 July 2006 in Germany, with about 3.2 million spectators in the stadiums and billions of viewers worldwide during the 64 matches. However, little is known about the incidence of cardiovascular events during such a great sport event. Herein, the increased risk of cardiovascular events for players and spectators regarding various soccer matches and tournaments is reviewed.

Exercise during soccer-games

Players

Playing soccer is comparable with a non-continuous exercise with intermittent phases of high physical intensity. The real playing time during a soccer match of 90 min is about 60 min, with an average energy consumption of 1500 kcal.1 The average distance per game is about 10 km with 10–20% covered at maximum speed and a maximal aerobic power of around 60–65 ml/kg/min oxygen uptake.2 This physical intensity is comparable to the maximum of young adult elite soccer players with an average aerobic capacity of 60 ml/kg/min oxygen uptake.3 Interestingly, there are differences in maximal workload depending on players position. Defenders have a slightly lower mean aerobic capacity and heart rate, with respect to midfielders or attackers (169 vs. 182 b.p.m.). Moreover, mean heart rate and aerobic power decline in the second half of a match by about 5%.3 In conclusion, average oxygen uptake for elite soccer players is around 70% of peak oxygen consumption, explained by the 200 short intense actions of players during a game.4 Moreover, blood and muscle lactate levels in soccer players are about 5–6 and 16 mM, respectively, with decrease of muscle glycogen of 50% after a friendly match.5

Referees

Referees should also have good physical condition regarding the physical and even mental requirements during a match. Italian professional referees cover an average distance of about 12.000 m.6 Approximately 1.800 m thereof were covered with a high intensity of more than 18 km/h. Additionally, about 1.000 m were run backwards. The average time without movement is 11 min during a match of 90 min.6 Although data are not available, referees have to cope with huge emotional stress in addition to the high physical requirements. Unclear situations during a match or wrong decisions certainly have an enormous influence on the autonomous nervous system with a potential impact on the cardiovascular system.

Physical activity and cardiovascular events

Regular physical activity of modest intensity is known to reduce the cardiovascular risk significantly in primary and secondary prevention.7 In contrast, cardiovascular events are associated with vigorous activities. Below the age of 30 years, exercise related incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD) is increased and associated with abnormalities as right ventricular dysplasia or coronary artery disease (CAD) and active myocarditis.7,8 Moreover, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is known to increase the risk of sudden death, and physical effort can provoke significant intraventricular gradients.9 Thus, in athletes with signs of a structural cardiac disease, echocardiography with physical or pharmacological stress testing is a valuable tool to detect certain high-risk patients.

In addition, left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH) as a structural and functional adaptation to increased wall stress is known to predict cardiac events and mortality.10 LVH even appears in athlete hearts, but with a normal systolic and diastolic function and a supranormal coronary vasodilator reserve.11 Especially high class soccer players are suggested to develop eccentric cardiac hypertrophy more likely compared to other sports, but training induced LVH is not supposed to increase the cardiovascular risk.1,12

Over the age of 30, almost all exercise related cardiovascular events are due to coronary heart disease. In these patients, submaximal exercise was shown to increase plasma viscosity, haematocrit, platelet count, and tissue plasminogen activator.13 Therefore, soccer-players, particularly with a silent cardiovascular disease, are supposed to be at an increased cardiovascular risk. However, a report of six SCDs in a 30-year-period in Croatia revealed a death rate among athletes of 0.15/100.000, whereas death rate in an exercise practicing population reached 0.74/100.000 (P < 0.001).8 In addition, a survey revealed that life expectancy is not decreased in male athletes.14

Emotional strain and cardiovascular events

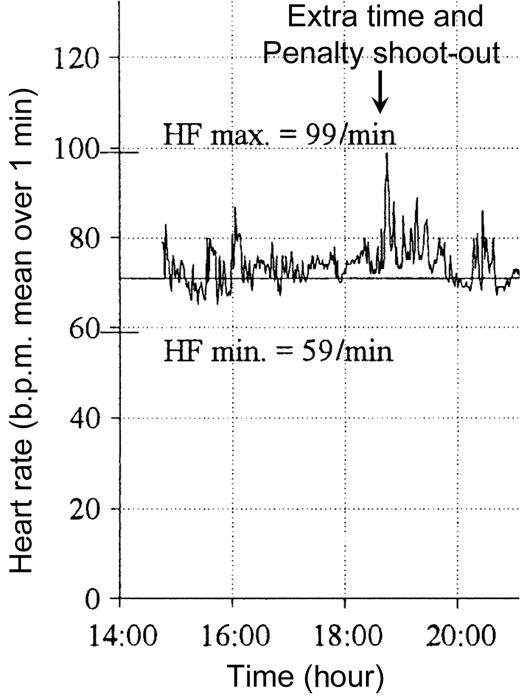

Obviously, spectators of a soccer match might not exhibit physical, but they rather experience psychological stress, likely dependent on the course or result of the match. During the quarterfinal of the FIFA World Cup 2006 (Germany against Argentina), a 24 h-ECG recorded the heart rate profile of a mother of one of the German players with a known coronary heart disease. While average heart rate of this day was 71 b.p.m., mean frequency increased up to 99 b.p.m. during the extra time and the penalty shoot-out without any cardiovascular symptoms (Figure 1). This indicates that thrilling scenes or disputable referee decisions are likely to increase sympathetic tone and catecholamine stimulation of the heart. Haemodynamic responses include an increase of heart rate, vascular resistance, and blood pressure with consecutively enhanced cardiac oxygen demand and vascular shear stress probably potentiating frequency of plaque rupture in acute coronary syndromes. Moreover, the transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-subo-cardiomyopathy) is a known cardiovascular entity mimicking an acute myocardial infarction, which is related to emotional stress in about one-third of all patients.15 In 75% of patients with a Tako-subo-cardiomyopathy, plasma catecholamine levels were increased. Therefore, catecholamine-mediated epicardial coronary spasms or myocyte injuries were suggested to be involved as pathophysiological mechanisms. Thus, emotional strain is an important risk factor for cardiovascular events. In a highly competitive sport event, especially spectators with pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors or diseases are probably at an increased risk for cardiovascular events.

Profile of heart rate of a German players mother during the quarter final Germany against Argentina (5:3 after penalty shoot-out).

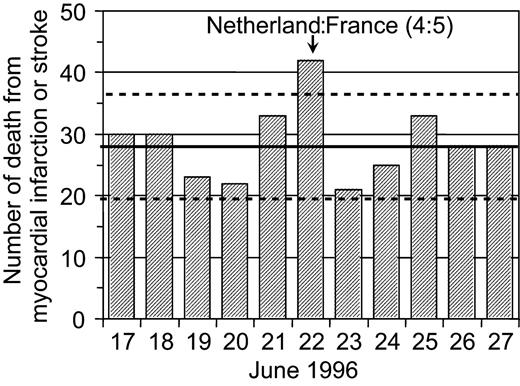

In a young Italian spectator with type I diabetes, continuous glucose monitoring during two consecutive days revealed significant increased blood glucose levels during the day of the half-final at the European Soccer Championship in 2000 (Italy against the Netherlands) without eating any additional food.16 Moreover, the transiently increased cardiovascular threat during a soccer match can last several days. During the FIFA World Cup in France in 1998, emergency admissions for acute myocardial infarction were increased in England for 2 days after the penalty elimination of England against Argentina (Table 1).17 In contrast, admissions for myocardial infarction, stroke, road traffic injury, or self harm did not alter after loosing or winning a match before. Thus, especially the high psychological strain during a penalty shoot-out seems to influence the cardiovascular system negatively with corresponding cardiovascular events in predisposed spectators. These results are consistent with findings in the Netherlands during the European Championship in 1996 in England. The quarterfinal was lost in the penalty-shoot out against France, with Clarence Seedorf misplaying the last penalty for the Netherlands. At this day, incidence of fatal myocardial infarction or stroke in men was significantly increased, while incidence in women did not change (Figure 2).18

Death from myocardial infarction or stroke in Dutch males in June 1996 during the Soccer European Championship.18

Observed and expected numbers of emergency admissions for acute myocardial infarction on day of the match and 5 days after England lost to Argentina by penalty shoot-out in 1998 Soccer World Cup17

| . | Number of admissions observed/expected . | Actual/expected . | Adjusted risk ratio . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day of match | 91/72 | 19 | 1.25 (0.99–1.57) |

| 1 day after | 88/72 | 16 | 1.21 (0.96–1.57) |

| 2 days after | 91/71 | 20 | 1.27 (1.01–1.61) |

| 3 days after | 76/74 | 2 | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) |

| 4 days after | 71/74 | − 3 | 0.92 (0.71–1.19) |

| 5 days after | 83/72 | 11 | 1.13 (0.89–1.43) |

| . | Number of admissions observed/expected . | Actual/expected . | Adjusted risk ratio . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day of match | 91/72 | 19 | 1.25 (0.99–1.57) |

| 1 day after | 88/72 | 16 | 1.21 (0.96–1.57) |

| 2 days after | 91/71 | 20 | 1.27 (1.01–1.61) |

| 3 days after | 76/74 | 2 | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) |

| 4 days after | 71/74 | − 3 | 0.92 (0.71–1.19) |

| 5 days after | 83/72 | 11 | 1.13 (0.89–1.43) |

Observed and expected numbers of emergency admissions for acute myocardial infarction on day of the match and 5 days after England lost to Argentina by penalty shoot-out in 1998 Soccer World Cup17

| . | Number of admissions observed/expected . | Actual/expected . | Adjusted risk ratio . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day of match | 91/72 | 19 | 1.25 (0.99–1.57) |

| 1 day after | 88/72 | 16 | 1.21 (0.96–1.57) |

| 2 days after | 91/71 | 20 | 1.27 (1.01–1.61) |

| 3 days after | 76/74 | 2 | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) |

| 4 days after | 71/74 | − 3 | 0.92 (0.71–1.19) |

| 5 days after | 83/72 | 11 | 1.13 (0.89–1.43) |

| . | Number of admissions observed/expected . | Actual/expected . | Adjusted risk ratio . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day of match | 91/72 | 19 | 1.25 (0.99–1.57) |

| 1 day after | 88/72 | 16 | 1.21 (0.96–1.57) |

| 2 days after | 91/71 | 20 | 1.27 (1.01–1.61) |

| 3 days after | 76/74 | 2 | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) |

| 4 days after | 71/74 | − 3 | 0.92 (0.71–1.19) |

| 5 days after | 83/72 | 11 | 1.13 (0.89–1.43) |

Incidence of SCD is known to be increased during psychological strain.19 Thus, SCD is suggested to be increased during a soccer match or tournament. Actually, total number of SCD was increased in the French-speaking population in Switzerland during the FIFA World Cup 2002 in Japan/South Korea compared to the period 1 year before (Table 2).20 Surprisingly, the significant increase in SCD could be observed in both genders. Regarding the gender specific differences in frequency of cardiovascular events at the European Championships in 1996, one could reason that interest of females in soccer matches and especially championships increased over the last few years.

Number of sudden cardiac deaths in the French-speaking population in Switzerland during the soccer World Cup 2002 and the same period 1 year before20

| . | 31 May 2001–30 June 2001 . | World Cup 31 May 2002–30 June 2002 . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of sudden cardiac deaths | 38 | 62 | 0.02 |

| Males, n (% total) | 26 (68%) | 46 (74%) | 0.01 |

| Females, n (% total) | 12 (32%) | 16 (26%) | 0.02 |

| . | 31 May 2001–30 June 2001 . | World Cup 31 May 2002–30 June 2002 . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of sudden cardiac deaths | 38 | 62 | 0.02 |

| Males, n (% total) | 26 (68%) | 46 (74%) | 0.01 |

| Females, n (% total) | 12 (32%) | 16 (26%) | 0.02 |

Number of sudden cardiac deaths in the French-speaking population in Switzerland during the soccer World Cup 2002 and the same period 1 year before20

| . | 31 May 2001–30 June 2001 . | World Cup 31 May 2002–30 June 2002 . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of sudden cardiac deaths | 38 | 62 | 0.02 |

| Males, n (% total) | 26 (68%) | 46 (74%) | 0.01 |

| Females, n (% total) | 12 (32%) | 16 (26%) | 0.02 |

| . | 31 May 2001–30 June 2001 . | World Cup 31 May 2002–30 June 2002 . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of sudden cardiac deaths | 38 | 62 | 0.02 |

| Males, n (% total) | 26 (68%) | 46 (74%) | 0.01 |

| Females, n (% total) | 12 (32%) | 16 (26%) | 0.02 |

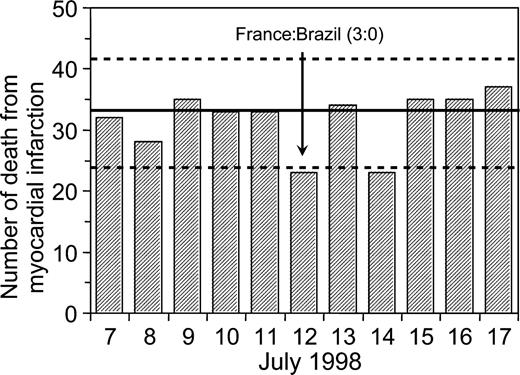

Although different effects of positive or negative emotional excitement are not clear, these results suggest an increased risk of cardiovascular events dependent on a specific soccer match or tournament, likely due to extended psychological stress in respect of loosing a match. However, positive emotional stress is thought to be without any negative influence on the cardiovascular system.21 In line with this suggestion were observations during the final match of the FIFA World Cup 1998 in France. The French players won the match against Brazil with 3:0. Consequently, number of deaths from myocardial infarction was significantly decreased in the male French population at this day (Figure 3).22

Death from myocardial infarction in French male in July 1998 during the Soccer World Championship.22

In conclusion, great and important sport events as a soccer European- or World‐Championship are afflicted with an increased physical stress in players and an enormous emotional strain for certain groups of spectators, especially in case of loosing of their favourite teams. Regarding this physiologicial and emotional strain, increased sympathetic tone and catecholamine levels are likely to influence the cardiovascular system negatively with subsequent cardiovascular events, particularly in cardiovascular high-risk patients. Thus, observation in a highly competitive sport event might provide insights into the impact of physical and emotional stress on cardiovascular events. With respect to the FIFA World Championship 2006 in Germany, cardiovascular events in players were not likely, because for the first time in history, all players had to undergo a standardized medical examination including echocardiography. Assessments of cardiovascular events in spectators are difficult, regarding the 3.2 million spectators in the stadiums, millions of spectators at ‘public viewing’ facilities and billions of spectators worldwide in front of the television. However, these data are extremely important and should be collected in prospectively designed national and international surveys.

Conflict of interest: none declared.