-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

CardioPulse Articles, European Heart Journal, Volume 36, Issue 9, 1 March 2015, Pages 532–538, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu520

Close - Share Icon Share

European Society of Cardiology launches Council on Hypertension

Hypertension is part of the core business of cardiovascular disease prevention and the Council will raise the risk factor's profile in the cardiology community

Inaugural nucleus board of the European Society of Cardiology Council on Hypertension (2014–16)

| Role . | Name . | Country . |

|---|---|---|

| Chair | Antonio Coca | Spain |

| Vice-chair | Bryan Williams | UK |

| Past-chair* | Renata Cifkova | Czech Republic |

| Secretary | Giovanni De Simone | Italy |

| Treasurer | Thomas Kahan | Sweden |

| Liaison officer | Michael Olsen | Denmark |

| Role . | Name . | Country . |

|---|---|---|

| Chair | Antonio Coca | Spain |

| Vice-chair | Bryan Williams | UK |

| Past-chair* | Renata Cifkova | Czech Republic |

| Secretary | Giovanni De Simone | Italy |

| Treasurer | Thomas Kahan | Sweden |

| Liaison officer | Michael Olsen | Denmark |

*Of the ESC Working Group on Hypertension and the Heart.

Inaugural nucleus board of the European Society of Cardiology Council on Hypertension (2014–16)

| Role . | Name . | Country . |

|---|---|---|

| Chair | Antonio Coca | Spain |

| Vice-chair | Bryan Williams | UK |

| Past-chair* | Renata Cifkova | Czech Republic |

| Secretary | Giovanni De Simone | Italy |

| Treasurer | Thomas Kahan | Sweden |

| Liaison officer | Michael Olsen | Denmark |

| Role . | Name . | Country . |

|---|---|---|

| Chair | Antonio Coca | Spain |

| Vice-chair | Bryan Williams | UK |

| Past-chair* | Renata Cifkova | Czech Republic |

| Secretary | Giovanni De Simone | Italy |

| Treasurer | Thomas Kahan | Sweden |

| Liaison officer | Michael Olsen | Denmark |

*Of the ESC Working Group on Hypertension and the Heart.

European Society of Cardiology Hypertension Council: Renata Cifkova, Giovanni de Simone, Bryan Williams, Antonio Coca, and Michael Olsen

The ESC Council on Hypertension was given the official green light at ESC Congress in Barcelona and held the inaugural meeting of the nucleus board in October. It has been 2 years in the making by hypertension experts who believed the specialty deserved a higher profile within the ESC.

Prof. Bryan Williams (London, UK) who led the proposal to develop the ESC Council on Hypertension and is the vice-chairperson of the new Council commented ‘for a number of years many cardiologists saw hypertension as something that was somewhat peripheral. Over the past two or three years, particularly with the emergence of device based therapy such as denervation for resistant hypertension, cardiologists have had renewed interest in hypertension as a clinical discipline’.

Cardiologists have expressed an interest in dedicated training sessions to better understand recent developments in hypertension and attendance at the hypertension sessions of ESC Congress has steadily grown. Williams says: ‘That gave us the impetus to say that this is an unmet need and there is a requirement for us to do something in this space at the most important cardiovascular meeting in the world’.

While there is still drug development for hypertension, the pace has slowed down over the past 10 years. But Williams points out that cardiologists need to stay abreast of new information. ‘There's still a huge amount of research work to be done in terms of deciding who to treat, when to treat, and how to treat patients’, he says. ‘And for devices, we need to determine how to best deploy and evaluate them. These things require a better understanding of the pathophysiology of hypertension’.

The ESC Council on Hypertension has evolved from the ESC Working Group on Hypertension and the Heart. Williams will be joined on the Council's inaugural board by chairperson Antonio Coca from Barcelona, Spain, and a who's who of experts from different countries (see box).

Antonio Coca will lead the board for the first 2 years and Williams will take over as chair for the following 2 years. Their job over the next 4 years will be to consolidate the Council, establish its terms of reference, and begin to develop educational programmes and symposia at ESC Congress and other meetings.

One of the initial anxieties around forming the Council was that it might undermine the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) but Williams stresses that these developments should be seen as complementary. ‘Our view is that the ESH caters predominantly to a clinical and research community that focuses entirely on hypertension and it's entirely appropriate that it remains strong’, he says. ‘But we also needed to ensure that the quality and profile of hypertension within ESC Congress was just as strong and one way of doing that was for the ESC to take control of that agenda by formulating a Council’.

One of the Council's first priorities is to continue developing the profile of hypertension within the ESC community with a particular focus on ESC Congress, which will be held in London next year. Both Williams and Coca are on the Congress Programme Committee, with Williams coordinating the hypertension section of the programme.

He says: ‘There's already recognition of the fact that as we've been working towards this Council over the past two years the overall quality of the programme for hypertension at ESC Congress has improved significantly. I'm hopeful that the meeting in London will reflect an even greater participation from people in the hypertension sessions and we want people to send their high quality abstracts to make the meeting as strong as possible’.

Beyond its involvement at ESC Congress, the Council will seek to have significant input into the development of ESC guidelines and position papers. Another aspiration is to create training sessions, master classes, and educational programmes in different parts of Europe. ‘Our big challenge will be to identify what topics are going to be popular and relevant and then make sure that these meetings are successful and have adequate financial support’, says Williams. ‘There's a lot of work to be done but we're confident, based on the interest in hypertension at ESC Congress, that subsequent focused sessions around different aspects of hypertension will be very popular with the cardiology community and beyond’.

He hopes that the new Council will encourage other professional groups with an interest in hypertension, including renal physicians, general physicians, clinical pharmacologists, and endocrinologists, to become part of the ESC community on a more regular basis. This could be through the dedicated symposia held at different times of year and at ESC Congress, where the structure of having themed villages for different topics makes it easy to spend the entire meeting in a particular specialty.

Williams is interested in raising the profile of ESC hypertension in other societies and countries internationally and, crucially, wants people to recognise that hypertension is still a major issue in cardiovascular disease prevention.

‘Most of the life years lost in patients with hypertension are due to cardiac disease’, he says. ‘As populations age and people are better treated with statins and smoking reduces, untreated and poorly treated hypertension will be the main residual risk factor for cardiovascular disease’.

Website for the ESC Council on Hypertension and sign up for membership: http://www.escardio.org/communities/councils/hypertension/Pages/welcome.aspx.

Jennifer Taylor Mphil

Guidelines on guidelines: interventions for heart disease Cochrane style

Physicians eager to advance some aspect of cardiovascular treatment might consider writing a Cochrane Systematic Review—which will give them a fine opportunity to master the literature, though they will find they must conform to a strict pattern, reportsBarry Shurlock PhD

The Cochrane Heart Group (CHG; www.heart.cochrane.org) is fast becoming the first-stop place to look for the latest analysis of the efficacy of interventions for cardiac disease. Up to 14 October 2014 it has published 49 reviews and a similar number of updates on a wide range of areas of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Since its inception >16 years ago (22 July 1998) it has been credited with >500 items in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), updated daily and published in the Wiley Online Library. These cover protocols for reviews being planned, the reviews themselves and the regular updates which authors are generally obliged to make. It is an impressive corpus of material for clinicians and others to draw upon, providing rigorously reviewed data for health professionals of all kinds to make decisions. In the context of Essential Evidence Plus, another product of John Wiley & Sons Ltd, it is becoming de rigueur for doctors of all kinds to navigate the huge medical literature. A licence/pay-wall protects the Cochrane Collaboration's material, but there are generous waivers for users from countries with limited resources.

Cochrane Heart Group is only one of the 53 specialty-based groups run by The Cochrane Collaboration.1 Others within the cardiovascular stable cover hypertension, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. The author base of the CHG comes from some 36 different countries, with the largest contingent from the UK, but sizeable corps from others, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, and the USA.

Central funding for this non-profit, non-governmental organization comes from a worldwide spread of national and international bodies of various kinds—universities, research institutes, charities, government departments, national research councils, health authorities and others.

The CHG is run from the Department of Non-Communicable Disease Epidemiology of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), London, UK. Here is based a team of editors and specialists, including statistical advisers, under the guiding hands of coordinating editors, epidemiologist Prof. Juan-Pablo Casas from LSHTM and the Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College, London, and his deputy, Dr Pablo Perel, senior lecturer at the LSHTM and ‘Senior Science Advisor to the World Heart Federation’.

All are involved in taking an idea for a review from an author, or authors, through a carefully orchestrated process that, if successful, ends with it being published online in the CDSR, perhaps also in a hard-copy journal. A US satellite of CHG is directed by cardiologist Dr Mark D. Huffman, assistant professor of Preventive Medicine and Medicine/Cardiology at the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, and there are other editorial hubs in a number of countries around the globe, including, in Europe, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain.

Describing the modus operandi of CHG, Dr Huffman said: ‘Professor Casas, Dr Perel and I meet [via email and Skype] once a month and consider the review proposal forms that have been sent in by authors – usually about 7 to 12 a month. We consider the motivation of the proposal, its objectives, the ability of the authors to achieve the goals, and also who's going to use it if it's published. We take on proposals that are likely to be used by clinicians and other “consumers”, that are well-written, with the question clearly defined. We also consider authors' backgrounds, and whether they have had previous experience of Cochrane systematic reviews. We accept about one-third of all proposals’.

At this early stage, potential authors are asked to check that the subject they are proposing is not already being covered by the CHG and to explain how the work would be carried out. Support by a single pharmaceutical company is not acceptable and reviews on classes of drug rather than a single product are preferred. Proposals from single authors are ‘not encouraged’ because of the need for duplication of tasks such as title screening and data extraction to minimize errors. Once accepted, the title is registered on ‘Archie’ (the Cochrane Collaboration's central server for manuscript control, named after Dr Archibald Cochrane) and authors are given 3 months to prepare a detailed protocol (which is then subjected to editorial and peer review). Authors whose protocol are accepted and revised are then published on the Cochrane Library by CHG.

The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions is packed with practical advice and a software package, Review Manager or RevMan, is available for preparing and maintaining the product. Also, staff at the LSHTM can help to define and execute strategies for searching the literature (in all languages) or give statistical support and there are 1-day training sessions held at regional centres around the globe. Those with the budget might even consider attending the annual Cochrane Colloquium, held in 2014 at Hyderabad, India, and planned for 2015 in Vienna, Austria.

Cochrane 22nd Colloquium, Hyderabad, India, 2014

The double-blind philosophy at the heart of randomized clinical trials has seeped into the Cochrane approach to writing reviews. Selection of trials—which is made not only on the basis of information published in papers, but may involve further information by personal contact with lead authors—is carried out independently by two of the authors, who then discuss differences. Similarly, data extraction from the sources is done by two authors and cross-checked. The scope of CHG is best appreciated by trawling the website, but recent reviews of interventions for CVD have covered fixed-dose combination therapy (polypills), stem cell therapy for chronic ischaemia and heart failure, statins for primary prevention, the Mediterranean diet, and oxygen therapy for MI. Reviews in progress include a comparison of cardiac-risk programmes based on health rather than just weight loss, exercise-based rehabilitation for atrial fibrillation, and reduced salt intake for heart failure.

It would be astonishing if a vast project like the Cochrane Collaboration did not have its detractors, based as it is on a fixed view of evidence-based medicine and a ‘best way’ of reviewing trials. Some have even accused it of ‘microfascism’, whatever that is. There is, of course, a risk of relying on one source of reviews, just as there is in relying on one clinical trial, no matter how well conducted. Dr Huffman accepts the point, though says that CHG only publishes ∼10–15 reviews a year, and a similar number of updates, [ED: 2011–2014] and sees no risk of it taking over the world yet. He said: ‘I'd be surprised if the CHG output approaches a quarter of all systematic reviews published on cardiovascular disease. There are an increasing number of systematic reviews and updates being published in the wider literature. Many of these however, may be based on observational studies that have a lower level of evidence, which can have their place, for example in defining risk. All our reviews consider only randomized clinical trials’.

Reference

New analysis of the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial

Key factors of the renal denervation may have contributed to the unexpected outcome

A new analysis of the renal denervation trial shows that the main results may have been affected by a number of confounding factors that partially explain the unexpected blood pressure responses in patients.

The analysis, published in the European Heart Journal,1 identified factors in the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial, such as variations in the performed procedure and changes in patients' medications and drug compliance, which may have had a significant impact on the results.

Results of the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial2 sent shock waves through the cardiology community and as a result, renal denervation procedures came to a halt.

Prof. Thomas Lüscher, editor-in-chief of the European Heart Journal, said: ‘SYMPLICITY HTN-3 resulted in referrals for the procedure drying up completely, making further trials almost impossible. However, in the analysis published in the European Heart Journal, David Kandzari and colleagues shed light for the first time on the interpretation of the results and suggest that in many patients the number of renal denervations was probably insufficient to achieve the proper degree of reduction in blood pressure that previous research had suggested was possible’.

Prof. Lüscher, who has co-authored an editorial3 to accompany Prof. Kandzari's paper, said: ‘Professor Kandzari's analysis shows there were significant variations in the way that patients in SYMPLICITY HTN-3 were ablated. His sub-analysis now shows, for the first time, that if patients received 12 or more ablations in the trial, they experienced the same blood pressure reduction as in the earlier, SYMPLICITY HTN-2 trial and as reported by a large number of registries’.

The analysis by Prof. Kandzari, director of interventional cardiology and chief scientific officer at Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta, USA, and his colleagues, showed that there was a link between the number of ablations and the subsequent reduction in blood pressure, because consistent and greater reductions in systolic blood pressure and heart rate were identified with a higher number of renal artery ablations. The sub-analysis also looked at variability in the way the renal denervation procedure was performed, and demonstrated greater decreases in systolic blood pressure depending upon ablation patterns.

‘For instance, patients who received between 11 and 14 or more renal ablations had reductions in systolic blood pressure (as measured during visits to the clinic) of 5–14 mmHg more than similar patients having the sham procedure. However, a greater effect of renal denervation compared with the sham procedure was not seen in patients who had ten or fewer ablations. Overall, the number of ablation attempts ranged from one to 26, with most patients receiving at least eight ablations. Giving four ablations in a spiral (helical) pattern in both renal arteries was also associated with greater reductions in systolic blood pressure, but this was only done in 19 patients’, said Prof. Kandzari.

‘These findings lead us to the hypothesis that the variability in how the procedure was performed may have contributed to the difference in efficacy seen in SYMPLICITY HTN-3 versus other SYMPLICITY studies. This opens the field for new trials confirming that more ablations delivered in a spiral pattern are able to provide effective denervation. With this new information, renal nerve ablation may recover and new trials can be performed, which may provide the evidence needed to back up anecdotal and registry evidence that the procedure can save patient’.

Other confounding factors were the changes to medications and patient compliance with their drugs. The protocol for the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial specified that patients should be maintained on several anti-hypertensive medications at the highest possible doses, without any changes unless clinically necessary, from the time of enrolment to the end of the 6-month follow-up period. During this time, ∼40% of patients required medication changes; nearly 70% of those drug changes were due to patients experiencing adverse events or side-effects related to the maximally tolerated dosage of their hypertension medications.

‘The extent of these medication changes was not expected given the trial design, and it's important that we further evaluate if these frequent medication changes could have contributed to efficacy outcomes seen in SYMPLICITY HTN-3’, said Prof. Kandzari. ‘This analysis also suggests that changes in patient adherence to complex drug therapy could be another factor to partly explain the large blood pressure drop in patients who received the sham procedure. It was noted, for example, that a higher proportion of African Americans were prescribed vasodilator therapy, and marked reductions in blood pressure were seen in the sham group of African Americans in the trial’.

He concluded: ‘Though further research is necessary to ultimately determine the full clinical potential of renal denervation, these analyses are important to guide us in the right direction for future trials. With this new information, new trials can be performed that may provide the evidence needed to back up anecdotal and registry evidence that the procedure can potentially improve patient outcomes in hypertensive patients at risk of heart attacks and strokes’.

A podcast of the editorial by Felix Mahfoud and Thomas Lüscher is available at: http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/podcast

https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/european-heart-journal-podcast/id932795803.

E. Mason

A. Tofield

References

Renal denervation more successful when it includes accessory arteries

Renal denervation appears to be more successful at reducing blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension (HTN) when it includes accessory renal arteries, according to research presented at ESC Congress 2014 by Dr Linda Schmiedel from Germany.

Dr Schmiedel said: ‘More than one billion people worldwide suffer from arterial hypertension. Up to 15% of patients suffer from resistant hypertension (rHTN) and are unable to reduce BP below 140/90 mmHg despite adhering to full doses of an appropriate three drug treatment regimen including diuretics. The prevalence and prognosis of rHTN is still unknown, but we do know that cardiovascular risk doubles with each BP increment of 20/10 mmHg. Effective treatment is therefore vital, especially in patients with rHTN.’

Renal sympathetic denervation (RDN) has been established as an effective treatment for these patients since 2009. The procedure is feasible in these arteries because of their size (>20 mm long and 4 mm in diameter). Renal sympathetic denervation has shown promising results with BP reductions of 23/11 mmHg in previous studies.

However, until now, RDN has not been performed in the accessory renal arteries due to their small diameter and the risk of developing a vascular stenosis after catheter ablation.

The aim of the current study was to examine whether complete ablation by performing RDN in accessory renal arteries, in addition to the main renal arteries, would influence blood pressure even more in patients with rHTN. The study included 110 patients with rHTN. At the beginning of the study, mean ambulatory BP was 154 ± 10/85 ± 9 mmHg and patients were taking more than six drugs to treat their hypertension.

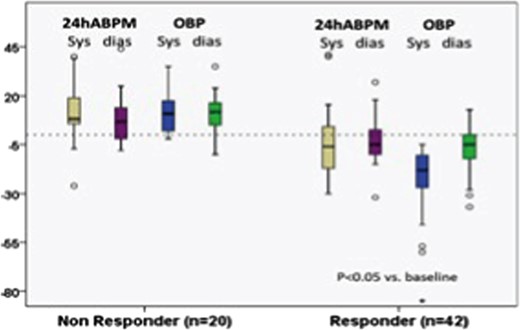

Six months after RDN, 62 patients were available for follow-up and had office BP (OBP) and 24 h ambulatory BP (ABPM) measurements taken. Overall, the procedure was successful in 42 patients (67%) with a corresponding drop in BP of >10 mmHg (Figure 1). Of these patients, 34 (54.8%) had ablation in the main and accessory arteries.

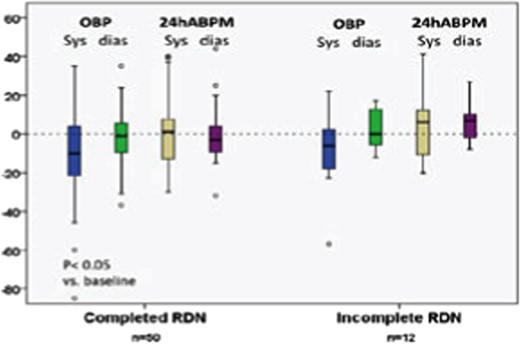

Of the 62 patients available at follow-up, 12 (19%) had accessory renal arteries that were not completely ablated. The success of RDN was compared between those whose ablation was complete (including main and accessory arteries) and those whose ablation was incomplete (main arteries only). Patients with complete ablation had a greater BP reduction with RDN (18 ± 4/−5 ± 2 mmHg) compared with those whose ablation was incomplete (12 ± 8/3 ± 4 mmHg) but the difference was not significant (P = 0.67) (Figure 2).

Patients with complete ablation had greater BP reduction with RDN.

It was found that complete ablation produced a trend for more BP reduction, although it was not significant, perhaps due to the small number of patients.

She concluded: ‘Further investigations focused on the role of accessory renal arteries and the completeness of the RDN procedure are needed to confirm our results.’

ESC Press Office

Energy drinks can cause heart problems

Prof. Milou-Daniel Drici, France, presented research at ESC Congress for the ‘caffeine syndrome’

‘So-called “energy drinks” are popular in dance clubs and during physical exercise, with people sometimes consuming a several drinks consecutively. The situation can lead to a number of adverse conditions including angina, arrhythmia and even sudden death’.

He added: ‘Around 96% of these drinks contain caffeine, with a typical 0.25 litre can holding 2 espressos worth of caffeine. Caffeine is one of the most potent agonists of the ryanodine receptors and leads to a massive release of calcium within cardiac cells. This can cause arrhythmias, but also has effects on the myocardial contractility and oxygen utilization. In addition, 52% of drinks contain taurine, 33% have glucuronolactone and 66% contain vitamins’.

Dr Drici continued: ‘In 2008 energy drinks were granted marketing authorisation in France. In 2009 this was accompanied by a national nutritional surveillance scheme which required national health agencies and regional centres to send information on spontaneously reported adverse events to the A.N.S.E.S, the French agency for food safety’.

The current study analysed adverse events reported to the agency between 1 January 2009 and 30 November 2012. Some 15 specialists including cardiologists, psychiatrists, neurologists, and physiologists contributed to the investigation. The findings were compared with published data in the scientific literature.

The researchers found that consumption of the 103 energy drinks in France increased by 30% between 2009 and 2011 to over 30 million litres. The leading brand made up 40% of energy drinks consumed. Two-thirds of drinks were consumed away from home.

During the 2-year period, 257 cases were reported to the agency, of which 212 provided sufficient information for food and drug safety evaluation. The experts found that 95 of the reported adverse events had cardiovascular symptoms, 74 psychiatric, and 57 neurological, sometimes overlapping. Cardiac arrests and sudden or unexplained deaths occurred at least in 8 cases, while 46 people had rhythm disorders, 13 had angina, and 3 had hypertension.

Dr Drici said: ‘We found that “caffeine syndrome” was the most common problem, occurring in 60 people. It is characterised by tachycardia, tremor, anxiety and headache. Rare but severe adverse events were also associated with these drinks, such as sudden or unexplained death, arrhythmia and myocardial infarction. Our literature search confirmed that these conditions can be related to the consumption of energy drinks’.

He added: ‘Patients with cardiac conditions including angina, catecholaminergic arrhythmias and long QT syndrome should be aware of the potential danger of a large caffeine intake, which can exacerbate their condition with possibly fatal consequences’.

He concluded: ‘Patients rarely mention consumption of energy drinks to their doctors unless they are asked. Doctors should warn patients with cardiac conditions about the potential dangers of these drinks and ask young people in particular whether they consume such drinks on a regular basis or through binge drinking’.

ESC Press Office

Andros Tofield

People's corner: Roland Klingenberg MD FESC

A newly elected Fellow of European Society of Cardiology

Dr Roland Klingenberg is a board-certified internist and cardiologist working as a consultant in Acute Cardiology at University Hospital Zürich, Switzerland. A recently accredited fellow of the European Society of Cardiology, he combines clinical and scientific training across Europe. His major interests lie in the management of patients with acute coronary syndromes and gaining insights into the underlying pathogenesis with a focus on vascular inflammation and biomarkers.

Following graduation at University of Freiburg Medical School, Germany, in 2000, he began his residency in internal medicine and cardiology at University of Heidelberg, Germany (Prof. W. Kübler and Prof. H.A. Katus). Joining Prof. G.K. Hansson's laboratory at Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden in 2005 for a little >2 years with funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG) provided him with an excellent experience.

He specialized on inherent atheroprotective immunity carried by specific immune cells (regulatory T cells) and on approaches to make use of it for therapeutic purposes. In 2008, he joined Prof. T.F. Lüscher's team at University Hospital Zürich, Switzerland to complete his cardiology residency.

He had the privilege to be recruited into the consortium of the newly formed Swiss multi-centre consortium Special University Medicine Acute Coronary Syndromes (SPUM-ACS) with funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF), recruiting more than 2200 patients referred for coronary angiography between 2009 and 2012. As clinical investigator, he was responsible for patient recruitment, database management and organizing independent experts to adjudicate adverse events occurring during 12 months of follow-up (NCT01000701).

Dr Klingenberg's major research interest has been the evaluation of biomarkers in this cohort to improve risk stratification of patients and the identification of novel biomarkers including immune cells that may serve as novel therapeutic targets. Currently, he serves as study director of the CLEVER-ACS trial evaluating the impact of everolimus in patients with STEMI on infarct size, by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (NCT01529554).

Integrating science with patient management has been a very rewarding experience for him and he is greatly indebted to his tutors.