-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alexander Vonbank, Stefan Agewall, Keld Per Kjeldsen, Basil S. Lewis, Christian Torp-Pedersen, Claudio Ceconi, Christian Funck-Brentano, Juan Carlos Kaski, Alexander Niessner, Juan Tamargo, Thomas Walther, Sven Wassmann, Giuseppe Rosano, Harald Schmidt, Christoph H. Saely, Heinz Drexel, Comprehensive efforts to increase adherence to statin therapy, European Heart Journal, Volume 38, Issue 32, 21 August 2017, Pages 2473–2479, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw628

Close - Share Icon Share

Introduction—justification for a position paper

Previous work from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) and from other groups has addressed the benefits of statin treatment in different patient populations.1–4 Unfortunately, adherence to guideline-recommended statin therapy is suboptimal: Statins are underused and LDL cholesterol targets are not met in up to 80% of high-risk patients.5–7

Excellent reviews have recently been published on the issue of statin intolerance and some lay media as well strongly emphasize this issue.8 True and verified statin intolerance, however, is uncommon and is not the main reason for poor adherence to statin treatment. Because poor adherence to statin treatment in turn is extremely common, it appears necessary to discuss the problem of statin adherence in a broader context and to develop strategies to overcome it. This clinically important task has not yet been the focus of a review or practice recommendation and therefore is the aim of the present position paper from the ESC working group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy.

This work takes the position that statin therapy is underutilized because of non-adherence not solely related to statin side effects and proposes steps to be taken in cardiovascular practice to improve statin adherence and thus cardiovascular outcomes. Our article aims to highlight the scientific background that helps to (i) overcome statin non-adherence by definition and description of true adverse statin effects, (ii) increase statin adherence by changing reservation against lipid lowering in media and the public, and (iii) guide efforts in the scientific community to close the gap between knowledge and practice of lipid management.

Where do we stand: poor adherence to statin use

Although statins are generally well-tolerated, statin adherence is poor in clinical practice: A survey of statin prescription claims showed a 30% discontinuation rate within the first year following initial prescription for primary prevention in USA.9 Data from the Danish National Hospital Registry demonstrated that among patients started on statins only 11% took one package.10 Publications from Northern America reported statin adherence rates of 25% after initiation in primary prevention, of 36% in patients with CVD and of 40% in those with acute coronary syndromes, respectively. 5,7

Good adherence to guideline-recommended statin use has been proven to be associated with an improved outcome.11–13 In a systematic review of statin discontinuation in high-risk patients, Sandoval et al. reported that poor adherence and withdrawal of statin therapy led to increased cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular events and mortality both in primary and secondary prevention, as well as in the pre-operative setting. Specifically, statin discontinuation was associated with a 67% increased risk of an acute myocardial infarction, suggesting a potential rebound effect after statin withdrawal.14 However, also selection effects regarding the studied high-risk patients may explain this observation.14–16

Whether high-intensive statin therapy is associated with poorer adherence than standard statin therapy is controversial. In the Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering (IDEAL) study 17 which compared the effects of high-intensity atorvastatin (80 mg/day) and low-dose simvastatin (20 mg/day) on the occurrence of major coronary events, patients in the high-dose atorvastatin group more frequently discontinued study medication due to non-serious adverse events. However, IDEAL was an open-label study. Double-blind investigations such as the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy (PROVE-IT) or the Treating to New Target (TNT) trials did not confirm this observation.18,19 In observational investigations, long-term adherence to statins is minimally affected by statin potency among patients with established atherosclerosis, the group shown to derive the greatest absolute benefit from statin therapy.1,20TableS2 (see Supplementary material online) summarizes published data on statin adherence.

Poor statin adherence is a major cause of failure to achieve lipid goals. Many studies showed that there is a strong disparity between guidelines and clinical reality with regard to statin use and LDL-C goal attainment.6,21–24 A summary of published data on lipid goal attainment is provided in TableS3 (see Supplementary material online). It must be acknowledged, however, that poor lipid goal attainment to a great deal is due to physician inertia rather than poor patient adherence; physician inertia is therefore not the major focus of this work.

In search for explanations: obstacles to statin adherence

Adherence is defined as the extent to which a patient’s behaviour—taking medication or changing lifestyle—corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider.25 Adherence with drug therapy can be divided in into three components: First, acceptance and initiation of treatment; second, execution of treatment (i.e. how the drug is taken); and third, persistance of treatment over time.26 Accordingly, non-adherence encompasses poor initiation, poor execution (delayed or omitted drug intake), and poor persistence (intermittent or permanent discontinuation).27

Regarding initiation, Fischer et al.28 in an analysis of 195 930 electronic prescriptions found that lipid lowering therapy as a medication class was associated with primary non-adherence, which here was defined as the patient not initiating a first treatment even though the prescription had been written. These data reflect that 19.9% of prescribed lipid lowering medications were never filled. In line with this, other studies showed that almost one in six patients did not obtain their statin within 90 days from when it was prescribed.29,30 Compared with the patients who picked up their initial statin prescription, the patients who did not tended to be younger and healthier, with fewer co-morbidities, lower rates of hospitalization, fewer clinic visits and fewer current prescriptions. One reason for this primary non-adherence can be a general aversion against or discomfort with swallowing tablets. Indeed, it is important to recognize that for most patients having to take medication on a long-term basis is not a trivial issue. This is also referred to as medication disutility, and has been recently investigated by Fontana et al. 31 in a primary prevention setting.

With respect to the prevalence of execution issues (delayed or omitted drug intake), no data are available in the statin literature; intensive research is necessary in this important field.

Discontinuation is a further important issue. While there is no single parameter to easily predict and resolve the issue of statin discontinuation, patient–physician and health system-related factors are known to increase discontinuation of statin therapy: in particular, use in primary prevention, new use, lower income status and fewer than two lipid tests performed significantly predict statin discontinuation.32–34

Reports in lay as well as in professional media are an important cause of statin discontinuation.35 Untoward effects of statins are frequently reported and typically overstated. A recent publication by Nielsen et al. in 674 900 individuals showed that early statin discontinuation increased with negative statin related news stories. Importantly, discontinuation was associated with a subsequently increased risk of myocardial infarction.36 Critical communications regarding statins often are scientifically unsound. For example it has been falsely claimed that well-conducted landmark trials like JUPITER are flawed by the industry, or that statins will cause breast cancer (which definitely is not the case).37 Possibly the safety issues with cerivastatin in the past 38 could be a reason for the critical discussion of the whole class of statins.

A more important reason probably is that statins are one of the most prescribed agents and that they are prescribed for long periods of time. Over the many years a patient takes a statin, some adverse events are likely to occur, whether or not they are causally related to the treatment. Of note, not only statin therapy is critically viewed but also other medical interventions of proven efficacy such as vaccination—a milestone in the history of medicine—are discussed very controversially in such media.39

Statins in general are very well-tolerated.8 The only three well-documented side effects attributable to statin therapy are muscle toxicity, including myalgia, myopathy and rhabdomyolysis, a moderate increase in diabetes risk, and increases of liver enzyme serum levels.8,40,41

Muscle symptoms with statin therapy should be considered in conjunction with an elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) concentration. Overall, statin myopathy tends to be overdiagnosed in clinical practice.42 Severe toxicity is particularly rare; 43 moreover, in randomized controlled trials, non-cardiovascular adverse event rates are not significantly different in statin and placebo groups, and are even lower than adverse event rates for other agents commonly used in CVD prevention, such as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, beta receptor blockers, or aspirin.44,45 Furthermore, the recent GAUSS-3 trial demonstrated that muscle-related statin intolerance was placebo controlled reproducible in a fraction of patients (47%) with supposed statin intolerance, but on the other side, 27% of the placebo group had also muscle symptoms. Moreover, the ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE showed similar results in a population of statin intolerant patients.46,47

An increase in new onset diabetes has been reported with statin treatment, but the risk is low in absolute terms and does not reduce the benefit regarding CVD event reduction:48,49 In a large meta-analysis, per one extra case of diabetes, 5.4 severe coronary events (coronary death, non-fatal MI) were prevented.50 Moreover, in patients without risk factors for developing diabetes, no increase of diabetes incidence was observed with statin treatment; among patients with such risk factors those who developed diabetes with statin treatment on an average did so only 5 weeks prior to those on placebo.51

The third documented side effect which may lead to discontinuation is elevation of liver enzymes.52 The placebo adjusted rate of significantly raised liver enzymes attributable to statins overall is low with ∼0.6 per 1000 patients.53,54 Further, there is good evidence supporting the view that statins do not induce organic liver disease.55 It has been impossible to causally attribute liver failure to statin use.55 A posthoc analysis of safety and efficacy of atorvastatin in the Greek Atorvastatin and Coronary Heart Disease Evaluation (GREACE) study even suggests that atorvastatin treatment can significantly improve liver enzymes in patients with abnormal elevations in AST and ALT levels during 3 years of follow-up.56 Most importantly, statin treatment has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events by 68% in patients with abnormal liver tests—a benefit greater than that seen in those with normal liver tests.57 An association between statin use and an increased cataract risk, was observed the recent HOPE 3 trial.58 However, a trial of ezetimibe plus statins reported fewer cases of cataracts in the active-treatment group than in the placebo group.59 Determining whether the excess in cataracts in HOPE-3 is truly related to the treatment requires a systematic analysis of statin trials.

Many other possible adverse effects are listed in the product information,60 but given the lack of confirmatory evidence from large placebo-controlled randomized trials, these are likely to be either very rare or not truly caused by statin treatment (at least at approved dosages). Of course, one cannot exclude that patients enrolled in clinical trials do not always represent the general target population, particularly elderly people with multiple co-morbidities and co-prescriptions, which may modify the tolerance profile of statins. Given the wealth of high-quality trial data on statin therapy, however, it appears extremely unlikely that clinically important statin side effects will emerge in the future. Whatsoever, also rare and unproven side effects may represent a considerable obstacle to statin adherence.61

Of note, previously assumed statin intolerance frequently does not recur when patients are rechallenged with statins.62,63 Thus we take the position that a trial of re-challenge is mandatory in most cases of suspected statin intolerance.

The increased incidence and prevalence of CVD in recent years has produced a great economic burden on total health care expenditure in many countries. This includes increased cost of prevention and, even more so, increased cost of treatment. Data from large-scale outcome studies have been used to conduct pharmaco-economic appraisals. Statin treatment was shown to be cost-effective in comparison with other health care interventions, and cost-effectiveness was related to the efficacy of the drug and the risk of cardiovascular disease at baseline.64 However, although the World Health Organisation (WHO) aimed at making statins and other drugs to prevent CVD available in 80% of communities, in some countries their availability and affordability is poor.65 Also this of course will reduce statin adherence.

Considering the paramount problem of statin underuse, there is ongoing discussion in some countries that statins should be made available without prescription. Despite the unquestioned benefits of statin treatment where it is indicated, however, there are a number of reasonable objections to offer statins to everyone. Although statins are remarkably safe, potential safety issues are best addressed by physicians.7,36,66

Potential solutions: what can we do?

As outlined earlier, non-adherence is a multifactorial problem which requires a multistep solution. Some intervention studies showed an improvement in adherence to statin medication. A personalized, patient-focused program involving frequent contact with health care professionals, or a combination of interventions has been shown to be most effective in improving adherence.67–70

Derose et al. investigated statin adherence in 5216 participants who had discontinued statin use within the past year. The intervention group received periodic automated telephone calls and, subsequently, had a significantly higher adherence to statin therapy within 1 year of intervention.71 Zullig et al.72 demonstrated that pre-filled blister packaging provides an inexpensive solution to improve medication adherence.

A Cochrane database review by Schedlbauer et al. concluded that reminding/re-enforcement appears to be the most promising intervention category to increase adherence to lipid lowering drugs. The studies included interventions that caused a change in adherence ranging from a 3% decrease to 25%.increase. Patient re-enforcement/reminding was investigated in six trials of which four showed improved adherence behaviour, with absolute increase rates of 24%, 9%, 8% and 6%, compared with baseline. Other interventions associated with increased adherence were simplification of the drug regimen (absolute adherence increase of 11%) as well as patient information and education (absolute increase of 13%).67 A MEDLINE database search from 1972 to June 2002 by Petrilla et al. identified studies of interventions designed to improve the compliance with lipid-lowering medications. The literature review yielded 62 studies describing 79 interventions. Personalized, patient-focused programs that involved frequent contact with health professionals or a combination of interventions were most effective at improving compliance.73 Less-intensive strategies, such as prescribing products that simplify the medication regimen or sending refill reminders, achieved smaller improvements in compliance.68 A recent meta-analysis showed a significantly approved adherence by using a polypill therapy instead of usual care in patients with CVD.74

All in all, repeated physician—patient contacts are effective to increase adherence. For practical patient management, the National Lipid Association (NLA) developed the Clinicians Toolkit, a guide to improve medication and lifestyle adherence. This toolkit provides a quick guide on how to identify patients at risk for non-adherence and list evidence-based interventions for improving patient adherence (https://www.lipid.org/sites/default/files/adherence_toolkit.pdf, 6 December 2016).

A minority of patients is truly statin intolerant. If suspected statin intolerance is confirmed on statin rechallenge, achieving guideline-recommended LDL cholesterol goals with other drugs than statins is indicated. Non-statin approaches such as ezetimibe have proven efficacious to reduce LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular events.46,47,75–77

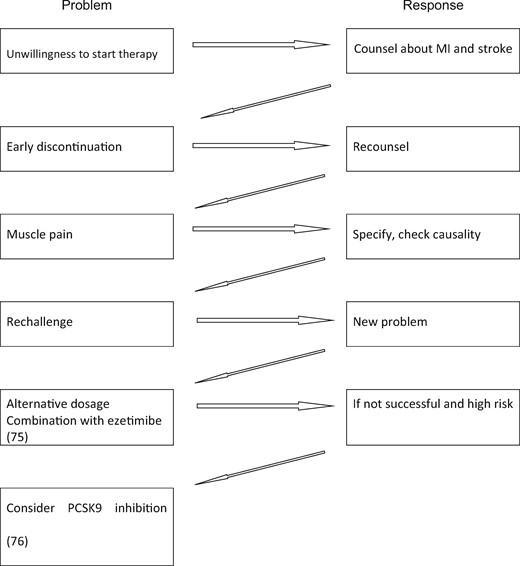

Published recommendations to improve statin adherence are summarized in Table 1. We suggest a stepwise approach to the problem of statins non-adherence, as is depicted in Figure 1.

| Goal . | Implementation . |

|---|---|

| Promote self-control | Encourage patients to assume an active role in their own treatment plans |

| Empower patients to become informed medication consumers | Establish a medication plan involving education of the patient and family members about the disease and medications |

| Stress medication benefits | Discuss the proven prevention of cardiovascular disease (e.g. MI and stroke) with statins. However, avoid fear tactics. Scaring patients can backfire and may actually worsen adherence |

| Support the patient to develop a list of goals | The goals should be realistic, achievable and individualized |

| Plan for regular follow-up | The doctor should interact with the patient at regular and brief intervals to reinforce the adherence plan |

| Implement a reward system | Giving positive feedback for successfully reaching a goal in the treatment plan |

| Reminder | Implement a telephone or pharmacy reminder system |

| Education tools | Use education tools like videos or apps |

| Packaging | Use prefilled blisters or unit dose packaging |

| Goal . | Implementation . |

|---|---|

| Promote self-control | Encourage patients to assume an active role in their own treatment plans |

| Empower patients to become informed medication consumers | Establish a medication plan involving education of the patient and family members about the disease and medications |

| Stress medication benefits | Discuss the proven prevention of cardiovascular disease (e.g. MI and stroke) with statins. However, avoid fear tactics. Scaring patients can backfire and may actually worsen adherence |

| Support the patient to develop a list of goals | The goals should be realistic, achievable and individualized |

| Plan for regular follow-up | The doctor should interact with the patient at regular and brief intervals to reinforce the adherence plan |

| Implement a reward system | Giving positive feedback for successfully reaching a goal in the treatment plan |

| Reminder | Implement a telephone or pharmacy reminder system |

| Education tools | Use education tools like videos or apps |

| Packaging | Use prefilled blisters or unit dose packaging |

| Goal . | Implementation . |

|---|---|

| Promote self-control | Encourage patients to assume an active role in their own treatment plans |

| Empower patients to become informed medication consumers | Establish a medication plan involving education of the patient and family members about the disease and medications |

| Stress medication benefits | Discuss the proven prevention of cardiovascular disease (e.g. MI and stroke) with statins. However, avoid fear tactics. Scaring patients can backfire and may actually worsen adherence |

| Support the patient to develop a list of goals | The goals should be realistic, achievable and individualized |

| Plan for regular follow-up | The doctor should interact with the patient at regular and brief intervals to reinforce the adherence plan |

| Implement a reward system | Giving positive feedback for successfully reaching a goal in the treatment plan |

| Reminder | Implement a telephone or pharmacy reminder system |

| Education tools | Use education tools like videos or apps |

| Packaging | Use prefilled blisters or unit dose packaging |

| Goal . | Implementation . |

|---|---|

| Promote self-control | Encourage patients to assume an active role in their own treatment plans |

| Empower patients to become informed medication consumers | Establish a medication plan involving education of the patient and family members about the disease and medications |

| Stress medication benefits | Discuss the proven prevention of cardiovascular disease (e.g. MI and stroke) with statins. However, avoid fear tactics. Scaring patients can backfire and may actually worsen adherence |

| Support the patient to develop a list of goals | The goals should be realistic, achievable and individualized |

| Plan for regular follow-up | The doctor should interact with the patient at regular and brief intervals to reinforce the adherence plan |

| Implement a reward system | Giving positive feedback for successfully reaching a goal in the treatment plan |

| Reminder | Implement a telephone or pharmacy reminder system |

| Education tools | Use education tools like videos or apps |

| Packaging | Use prefilled blisters or unit dose packaging |

Flow chart of problems arising with statin therapy and proposed solutions.

Conclusion

There is compelling evidence that statin therapy improves cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Unfortunately, statin adherence is far from optimal regarding initiation, execution and persistence of treatment over time.26 Poor adherence to statin therapy is associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality. Evidence-based steps to improve adherence are available and should be taken in order to improve patient outcomes. Reinforcing statin adherence appears to have at least as strong beneficial effects as introducing a new drug.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

Example of lay press with statin flwed trials. http://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2015/08/26/statin-flawed-studies.aspx (6 December 2016).

The History of Vaccination. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/pages/the-history-of-vaccination.aspx (6 December 2016).

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.